How Much?

How much would I have to pay you to purposefully harm poor children in America? An offensive question to most American teachers, I suppose.

In 1961, Yale University psychologist Dr. Stanley Milgram conducted a now-famous study in which he tried to understand what kind of people he could get to do what they believed was causing great harm to another human. He ran an ad in the New Haven newspaper asking people to take part in an experiment that would last one hour and for which they would be paid $4.50. While waiting for their turn, subjects would chat with another participant about the upcoming job. This other person was actually a confederate of the research team. Next, a scientist in a lab jacket would appear and ask each subject to draw a slip of paper out of a hat to determine who would be the “teacher” and who would be the “learner”. The research subject always got the role of teacher.

In the presence of the subject, the scientist would then strap electrodes onto the confederate, then move to an adjoining room where there was a machine that was said to deliver electronic shocks to the confederate. The stated goal of the experiment was to measure the impact of negative reinforcement on learning. A word pair memory activity was used. Each time the learner gave a wrong answer, a “shock” was administered by the subject. With each wrong answer the “voltage” was increased. With the first shock came a grunt. With the second shock came a mild protest. Next, stronger protests. Then screaming and shouting. Then screaming and banging on the walls. Then, when the voltage levels indicated more than 315 volts, the subject would hear nothing but silence. Of course, there were no real shocks being administered to the confederate, but the subject believed them to be real.

Milgram asked social psychologists to predict the results of this study. They predicted that only 1.2 % of subjects would give the maximum voltage. As it turned out, 65% did (Milgram, 1963, 1974).

Many teachers have told me that they are “required” to cover excessive content, keep up with a rigid pacing guide, or teach using a scripted learning program in which every child gets the same lesson on the same day in the same way, in spite of the very different levels of readiness among these children. Teachers have told me they have been “directed” to cut recess, art, and play from their schedules. Teachers have told me that they clearly know which kids are frustrated, afraid, overwhelmed, or bored as they mechanically deliver their prescribed content. And some teachers never even consider the readiness levels of their students as they race through content, test and grade their students, then race on to the next chapter or lesson.

For decades American schools have been engaged in a failed experiment, attempting to cram more content into a typical teaching day than humanly possible, asking children to learn overwhelming content at younger and younger ages without taking the time to build the foundation skills needed for learning success or behavioral success. We’ve created anxiety-filled classrooms in which children are less likely to fall deeply in love with learning. We’ve done this even in the early childhood years, which are the most important learning phase in the life of a child.

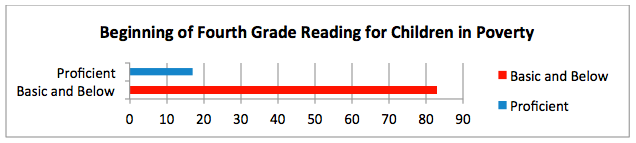

It’s not working. By the beginning of fourth grade, the point at which we can accurately predict long-term learning outcomes, only 33% of American children are at proficient reading levels. Only 17% of children who are eligible for free or reduced lunch are at proficient reading levels. The vast majority of these children are unlikely to become good readers, love to learn, go on to advanced education, or become learners for life.

How much are they paying you? Is it enough?